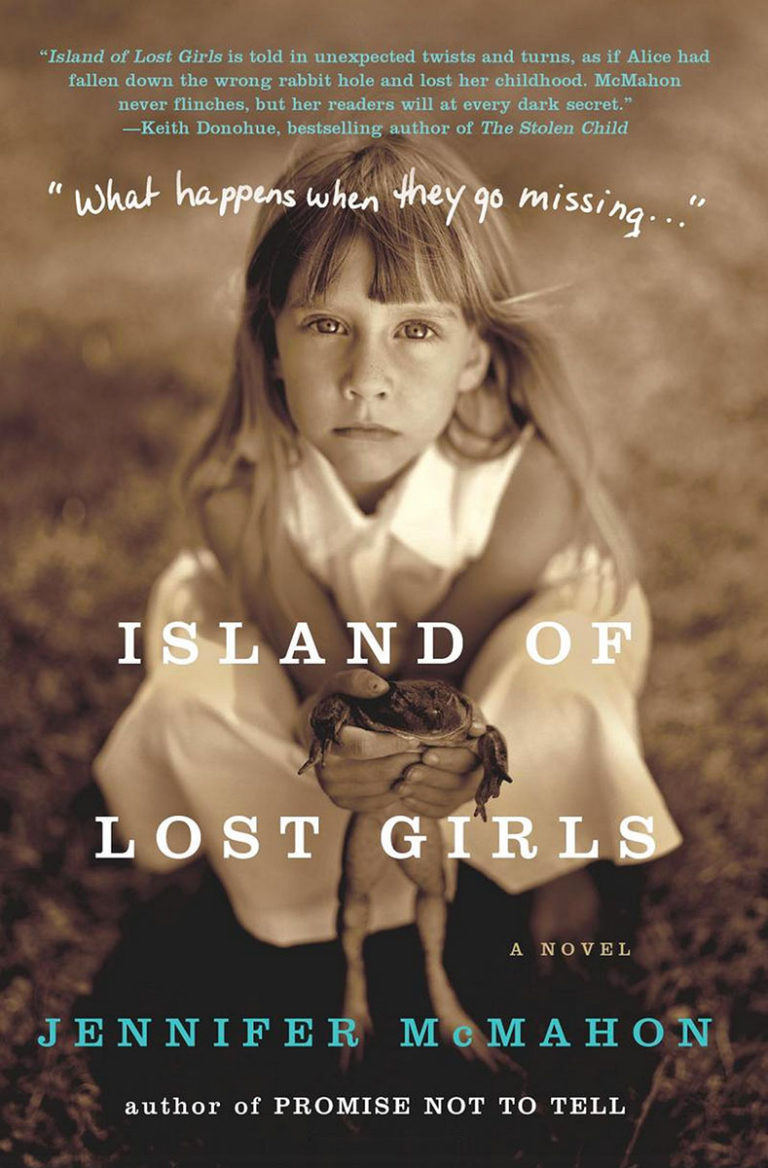

Island of Lost Girls

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop, IndieBound

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop, IndieBoundPublished by: William Morrow Paperbacks

Release Date: April 22, 2008

Pages: 272

ISBN13: 978-0061445880

Overview

A New York Times bestseller

One summer day, at a gas station in a small Vermont town, six-year-old Ernestine Florucci is abducted by a person wearing a rabbit suit while her mother is buying lottery tickets. Twenty-three year old Rhonda Farr is the only witness, and she does nothing as she watches the scene unfold – little Ernie goes with the rabbit so casually, confidently getting into the rabbit’s Volkswagen bug, smiling while the rabbit carefully fastens her seatbelt.

The police are skeptical of Rhonda’s story and Ernie’s mother blames her outright. The kidnapping forces Rhonda to face another disappearance, that of her best friend from childhood – Lizzy Shale, whose brother, Peter just so happens to be a prime suspect in Ernie’s abduction.

Unraveling the present mystery plunges Rhonda headlong down the rabbit hole of her past. She must struggle to makes sense of the loss of the two girls, and to ask herself if the Peter she grew up with — and has secretly loved all her life — could have a much darker side.

Praise

“Island of Lost Girls is an unsettling account of the secret lives of children, told in unexpected twists and turns, as if Alice had fallen down the wrong rabbit hole and lost her childhood. McMahon never flinches, but her readers will at every dark secret.”

—Keith Donohue, author of The Stolen Child

“Like The Lovely Bones, despite grim and nearly unbearable subject matter, this book is un-put-downable from page 1. The writing is exquisite and often very funny, and themes of childhood and loss resonate.”

—The Boston Globe

“This smart mystery-thriller grabs you by the throat and won’t let go…. Echoes of Alice down the rabbit hole persist right through the spellbinding conclusion, making this a page-turner you’ll neglect sleep for.”

—People

“Haunting… McMahon expertly shifts between pivotal events in the past and present-day action, building tension to a resolution both poignant and shattering.”

—Publishers Weekly

“As in her assured debut novel, McMahon offers a moving if bittersweet portrait of childhood… readers will be hooked on both the mystery element and the coming-of-age aspects of this atmospheric novel.”

—Booklist

“Well-crafted… dirty family secrets and sudden plot twists harken back to McMahon’s debut.”

—Kirkus

“A heartbreaking and haunting masterpiece…. the plot twists and turns and tantalizes.”

—Bookreporter

Backstory

I wrote the first draft of Island of Lost Girls before writing Promise Not to Tell. I worked hard on it for over a year, trying to create a multi-generational family saga told from many points of view. Unfortunately, the resulting book was such a mess that I was ashamed to show it to anyone. A couple of years later, while my agent was trying to sell Promise Not to Tell, I dug out my family saga, polished it up a bit and sent it off to my agent. He agreed that it was unwieldy, and suggested that the first and most important thing I needed I to do was decided whose story I was going to focus on. Once I decided that it would be Rhonda’s story, things began to fall into place. I ended up throwing about half of that original draft away.

The original inspiration for Island of Lost Girls was simple: I had stopped at a gas station in a little town near a state forest in Vermont. A woman pulled into the parking lot, left her car running, and ran into the store. I noticed a little girl strapped into the backseat. Immediately, my mind started inventing these terrible scenarios: what if someone came along, jumped in the car, and drove off with the girl– what would I do? Would I try to stop them? My mind said, of course I would. But what if it was stranger than that; what if it was someone in a costume: Santa, a clown, the Easter Bunny? Would people believe me? The woman came out of the store in a couple of minutes, a pack of cigarettes in her hand and drove off, the girl safe in the backseat. But the seed of a story was planted, and an abduction much like the one I fretted about ended up being the event that sets everything in motion in the final version of Island.

Here’s another fun fact – I once had a job at a family farm and was asked to play the Easter Bunny for a couple of weekends. I put on the dingy white suit with the mesh eyes, stood by the side of the road waving at cars, hugging small children and giving them balloons and lollipops. It was a very odd and disconcerting experience and I think the thing that got to me most was how much these tiny kids trusted me, how excited they were to see me and give me hugs when really, I could have been anyone in that suit. I definitely drew on this experience when writing Island.

Excerpt

“Hello there!”

Suzy’s shoulders jerked when she heard the voice. It was the voice of a tired man, a man stuck on land, a man who clearly didn’t know she was miles underwater now and wouldn’t be able to hear him. Suzy wasn’t supposed to talk to strangers. She knew what could happen if you did. You could end up like Ernestine Florucci, who had been in the second grade with Suzy, and now might be gone forever. Even though they lived in Vermont — where, Suzy now realized listening to the grownups, things like that weren’t supposed to happen. Like living in Vermont was a vaccine against bad things.

She pulled the dive lever on the sub and sank further, thought about something she’d seen on the news last week, something about Ernestine, but her daddy had jumped up and turned the TV off before Suzy could hear. The news man in the blue suit was saying something about a confession, which Suzy knew was when you went into a little room with a priest with a white collar. Then the TV snapped off and her parents talked in hushed voices. They had all gone out for creemees – Suzy got a chocolate-maple twist with extra chocolate sprinkles.

“Whatchya doing there?” the man asked Suzy, his voice friendly. He was right beside her now, his hands resting on the chipped red door. He was wearing a green jacket with a badge pinned to the front and carrying a walkie-talkie. This man was a police officer. He had a gun and everything.

She squinted up at him, the light from the midday sun behind the trees behind him giving him a kind of glow like an angel, like the way the world sometimes looked just before a seizure, like everything had this halo, everything holy.

Suzy heard the sound of dogs barking, coming nearer, men talking, their footsteps cracking twigs, the cold squawk of staticky voices on walkie-talkies. They were coming up the pine-needle covered path that led down to the lake. Was she being arrested? Had her parents sent the police to see if she was playing where she was not supposed to?

“What’s your name?” asked the man. He had short dark hair, a little dimple in his chin. “You live near hear?”

She was allowed to talk to police officers. She was pretty sure. Suzy blinked.

“My name’s Joe,” he said, extending his hand. She stuck out hers to shake.

His hand was soft and warm, smooth as the skin of a baseball glove. She gave in and told him her name.

“That’s a real pretty name for a real pretty girl.”

She hated this talk — this pretty girl, pretty name, pretty hair, pretty ribbon, “you look just like a little angel” talk adults gave. She hated the winks, the nods, the little pats on her head, testing the bounce of her curls.

The dogs were there then and men in uniforms, men in wide-brimmed hats kicking at leaves, looking at the ground, letting the dogs pull them around. Big German shepherd dogs, police dogs, dogs that could bite, could crush your hand. Suzy had seen a program on TV about a man who couldn’t see and needed a dog to help him. A special dog who helped him cross streets, get on buses, do his shopping. Smart dogs, German shepherds.

These police dogs were over at the pile of rotten wood, the boards with nails that could give you lockjaw, and they were whining, barking, digging at the ground like there was hamburger underneath, some sweet dog treat. Or maybe it was drugs. Dogs could sniff drugs, she knew this from school, from Officer Friendly who brought his trusty dog Sam, the drug sniffer with him. Sam wore a leather harness like the blind man’s dog, like maybe Officer Friendly was blind, blind to drugs, to danger even, without Sam. Dogs could smell hundreds of times better than humans. Dogs could smell things miles away. Dogs were faithful and friendly and loyal. Dogs drooled. Their feet smelled like Fritos. Their breath could smell rotten like something got caught in their throat and died.

The men in uniforms were pulling at the boards, someone was taking pictures, someone had a video camera. Maybe they were all in a movie, a movie like her Nana Laura Lee had been in. They were all movie stars.

“So where do you live, Suzy?” asked Joe. She told him. She told him her grandma’s house was on the other side of the trees there, but that her grandma didn’t really live there, she lived far away in a hotel for people who took medicine for their heads. Her daddy was fixing screens on the windows because they were selling the house. She told him that when Daddy was done, they would visit Nana Laura Lee who lived down by the lake in a faded pink trailer with a hundred bird feeders outside. Nana Laura Lee loved birds. Laura Lee had a white submarine in her yard that was actually a propane gas tank, but ever since Suzy was small, she believed it was a special private submarine for exploring the bottom of the lake. Laura Lee was a little crazy, that’s what Suzy’s daddy said, but Suzy’s mom explained that everyone was really a little crazy once you knew them.

Even Suzy’s own mom and dad were crazy, she guessed. They had played in these woods as kids. The pile of rotten boards was once a stage where Mommy had been a crocodile and Daddy was Peter Pan.

The policeman was still talking to her, asking her how often she came out to the woods, how old she was, what grade she was in, if her daddy knew where she was. One of the men in a green and tan uniform called to him.

“Sergeant Crowley, we found something!”

And the Sergeant named Joe went over, walked through the circle of men and eager barking dogs, got down on his knees and peered into the hole that had been covered by the wood the men had pulled away.

“Call forensics,” he said. “I want the whole team out here. And rope this area off! Now!”

The baby mice squeaked for food, for their mama, and Suzy told them to hush, there were dogs around. She got out of the Impala, hopped over the door which had been stuck closed for years, and snuck up behind the men. She got down on her hands and knees, peered through the legs of one of the men and saw something down in the hole — some old clothes, dirty, red and torn; and just when it was coming into focus, just when she saw it had eyes, it had teeth, and scraps of hair, Sergeant Joe was swooping her up, saying this was no place for little girls, asking her to point to where her daddy was, saying not to be scared, that he was going to take her home.